Not All Arguments Are Equal

We’ve had our first Iraq War death this week in our usually sleepy little town in the middle of the corn and soybean fields of northcentral Indiana. A young marine, recently graduated from Manchester High School and recently married to his high school sweetheart, was riding in a vehicle when it hit a mine near Fallujah. The news spread quickly and widely before church early Sunday morning, as the two local families devasted by the explosion were both large and active in a wide variety of ways here. There will be a funeral, probably an overflowing one, with flags and an honor guard, and the entire town will mourn.

Arguments will be put aside during this time of mourning, and I do not intend to argue here. But, (oh yes, there is always a “but,” as my students well know), I needed a little solace of my own, being the father of three draft-aged children and a Veteran of a Foreign War myself (as are all veterans who served overseas in a time of war). Playing around with Google as I did a little research to see what others far wiser than I have said about war and death, I found this breathtaking quote from President Jimmy Carter: ”War may sometimes be a necessary evil. But no matter how necessary, it is always an evil, never a good. We will not learn how to live together in peace by killing each other's children.”

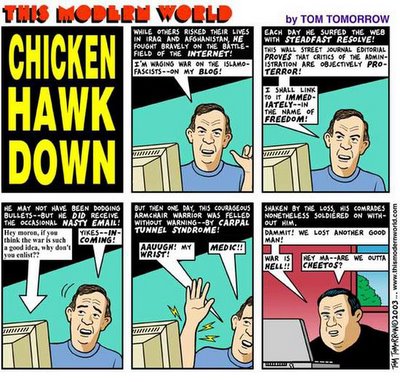

President Carter knows a few things about war. A Navy veteran himself, he oversaw some pretty nasty stuff in Iran during his presidency. So when he makes an argument about war and peace, when he vividly implies that sending our children to die in neighboring Iraq is not a guarantor of peace, either at home or in the Middle East, he’s not just shooting off his mouth, unlike the Chickenhawks who dominate today’s punditocracy. (A Chickenhawk, briefly put, is a journalist or a politician who urges other parents to send their sons and daughters to war but passed on the chance for him or herself. Dick Cheney and Rush Limbaugh are two of this country’s most famous.)

I pointed out by e-mail to uber-pundit Jonah Goldberg several weeks ago that I found his arguments for the war in Iraq a little perturbing, in fact, without merit, because I didn’t see him as a qualified source. Of the right age to have happily served in the first Iraq war, and still much younger than the many fathers and grandfathers currently serving over there, his arguments for bringing democracy to the troubled Middle East at the point of a bayonet (the right metaphor escapes me today, maybe I mean in the bombsite of an F16 fighter jet) seem hypocritical at best and cowardly at worst, I told him. Naturally I didn’t receive a reply, but I was amused and pleasantly surprised several weeks hence when he wrote a tortuous column explaining why even though he never donned a uniform or trained with an M16, he was nonetheless quite qualified to write of the necessity to spill the blood of other peoples’ sons and daughters in pursuit of his own pet projects. I wasn’t asking him if he were qualified, however, I was simply pointing out that because his arguments are both morally and ethically bankrupt, as evidenced by his own avoidance of any direct suffering in so-called support of the troops, they are likely to be intellectually bankrupt too. (And yes, I know, President Bill Clinton was a “draft dodger,” but he openly protested the Vietnam War on behalf of ALL draft-aged men and women and then as President was very reluctant to send troops into harms way without a clear and compelling need. I do not see any disconnect there whatsoever.)

My own point here though, is not that Goldberg and others like him are or are not qualified to opine about the war. Rather, as I tell my students, whenever reading and contemplating what someone else is arguing, it is necessary to do your own research on that writer, to try to learn for what reasons that writer may see things as they do. The fox, for example, may argue quite convincingly that he has the right qualifications to guard the hen house (sharp teeth, keen sense of smell, superior night vision, etc.). But unless you find out ahead of time that his favorite meal is chicken, I’d advise you not to be a chicken farmer!

Back to a more academic tone, this is the problem that faces all researchers: at what point does an author’s own bias become part of the research trail. Jane Tompkins has written brilliantly on this very conundrum, in her scholarly article titled “’Indians’: Textuality, Morality, and the Problems of History.” I assign this article the first week of class for all my ENG W233 students, as it brilliantly examines the conflicting accounts of the early contacts between the Native Americans and the first settlers through the eyes of those who recorded such contacts. Rather than trying to determine the veracity of those accounts, rather than hoping to sort out the conflicts, she instead studies the backgrounds and interests of those who recorded those accounts, coming up with a fascinating analysis of the prisms through which they saw those encounters. Understanding those prisms, the glasses so to speak through which these recorders viewed their world, leads to an understanding of the encounters themselves, she argues.

It is Tompkins’ prisms which bring us back to the combat death of a 20 year old North Manchester man and to the title of this post, “Not all arguments are equal.” I’m hoping of course that there will be no arguments this week in North Manchester. This is a time of deep mourning, and acrimony and pomposity have no place. But when these arguments do erupt, as surely they will in time, it is not the rhetoric or even the facts that will determine the thrust of those proffered opinions, but rather the prisms through which these opinions are developed. To be honest, in this particular case, I think the only prism that matters is that of Scott Zubowski, and he’s dead. Everything else, for now at least, is hot air.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home