On Poetry and Pundits

Sometime in the late 60s I had the wonderful and life altering experience of hearing James Dickey read poetry at Duke University. What I most remember on that romantic undergraduate evening on Durham’s cloistered and magnolia shrouded “East Campus” is his lyrical recounting of a news story in which an airline stewardess fell from the inadvertently opened door of an Allegheny Airlines airplane flying over the expansive cornfields of the Midwest. The experience was life altering because Dickey, along with Duke University writer in residence Reynolds Price, taught me my own love of, and respect for, words and language.

Sometime in the late 60s I had the wonderful and life altering experience of hearing James Dickey read poetry at Duke University. What I most remember on that romantic undergraduate evening on Durham’s cloistered and magnolia shrouded “East Campus” is his lyrical recounting of a news story in which an airline stewardess fell from the inadvertently opened door of an Allegheny Airlines airplane flying over the expansive cornfields of the Midwest. The experience was life altering because Dickey, along with Duke University writer in residence Reynolds Price, taught me my own love of, and respect for, words and language. Hence it is with great pleasure that I read this week of his son, Newsweek writer Chris Dickey (only fathers can know of the incredible karmic mystery of a son following in his own footsteps), who described the media recently in light of the unfolding imbroglios connecting the culpability of the press to Patrick Fitzgerald’s federal grand jury investigation into the leak of the identity of CIA agent Valerie Plane, as a “marketplace that long ago concluded having access to power is more important than speaking truth to it.” For a moment just pause, and look at the language, surely a gift from his father: “truth to power.” Gives me shivers – the power of words.

Hence it is with great pleasure that I read this week of his son, Newsweek writer Chris Dickey (only fathers can know of the incredible karmic mystery of a son following in his own footsteps), who described the media recently in light of the unfolding imbroglios connecting the culpability of the press to Patrick Fitzgerald’s federal grand jury investigation into the leak of the identity of CIA agent Valerie Plane, as a “marketplace that long ago concluded having access to power is more important than speaking truth to it.” For a moment just pause, and look at the language, surely a gift from his father: “truth to power.” Gives me shivers – the power of words.

Lovely, you say, but what is my argument? Ah, my argument is about the quest for truth, and how language can illuminate or obscure this quest, depending on the motives of the speakers and writers.

Over coffee not to long ago, one of my students in my ENG W140 class (“Everything is an Argument”) asked me about the nature of postmodernism and what this still-controversial literary theory had to say about “truth.” His own assumption was that postmodernism holds there is no truth. Quite the contrary, I reported. Postmodernism is simply literary, political and economic theory that challenges the prevailing wisdom. Far from maintaining truth is not discernible, as some of my students seem to want to believe, or that truth is merely in the eyes of the beholder (see my previous post about Jane Tompkins), postmodernism postulates that we must ascertain motives before we can ascertain truth. That’s all.

This is nothing more than good research practice.

Take for example, J.M. Coetzee's literary masterpiece, Waiting for the Barbarians. A breathtaking portrait of history told, for a change, from the point of view of the conquered, this short novel challenges the basic foundational assumptions of a Western reader. Which exactly what postmodernism is about: a challenge to critical thinkers to re-examine their own points of view. Not necessarily to discard them, but to attempt the research into the historical and political archives that may indeed shed new light, let alone a rather brighter light, on cherished assumptions.

Another example: let’s all too briefly examine the rather amusing, new and very marketable “theory” about “Intelligent Design.” Widely understood to be a clever euphemism for the less politically correct word, “Creationism,” this new debate assumes that the great unwashed public simply has no understanding of science, let alone research. Insulting at best, and deceiving at worst, “Intelligent Design” postulates that words, rather than scientific research, can sway a debate. Why look at the facts, why examine the historical, geological, biological and zoological record, when one can just shout the loudest and use the cleverest language in the marketplace (back to Christopher Dickey) of ideas?

This of course is the challenge for my students, and for all good citizens of this great but ever more fragile democracy: how exactly does one look beyond the rhetoric?

Fortunately, thanks to the great libraries of the world, the answer is not that difficult. And the answer is exactly why the right wing media pundits like to accuse university professors of having a liberal bias: we teach students research, We teach them how to go to Ebscohost, LexisNexis and other academic databases to find their own answers to the great questions of these times. Truth is available. We just have to know how to formulate the questions (filtering for motives, qualifications, points of view) and where to look for the answers. And, of course, we have to be open to being pleasantly surprised when the answers don’t fit our own prevailing world view.

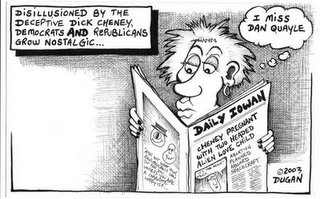

After all, as it was once said of Vice President and fellow Hoosier Dan Quayle, “a mind is a terrible thing to waste.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home