We developed this print in my J210 Warsaw class last week as part of a lesson on the history of photography. We’ve gotten as far as the camera obscura and camera lucida of the Renaissance and are sort of bogged down there as we try to get our own pinhole cameras to work. I’m trying to show the class how the next step was the development of fixed images using silver based salts. It’s hard of course to talk about one element of photography without talking about all the elements that go into a good picture, such as composition and lighting. A concurrent theme running through the class is the ethics and power of modern photo manipulation tools such as Picasa and Photoshop. This is appropriate on several levels, one simple one being that you can’t talk about lighting without talking about contrast.

I like the picture above because it is a useful example of several of the concepts I was trying to get across during our little darkroom episode. For one thing, the picture is part of my extensive collection of 8 by 10 inch negatives. I was able to pass around the class several examples, and because these negatives are so large, the students can more easily understand how the light activates and clumps the silver in the negative, turning that area of the negative black. And of course, just the fact it was taken with a camera so much larger and bulkier and heavier than today’s digital cameras fascinated the students. The picture also has historic value, in that it is nearly 40 years old and large format photography is rapidly fading out of existence.

And, as you can see here, the image is a careful study of light, form and composition similar to the painted nudes of the late Renaissance artists and early Impressionists. One of the concepts I’m trying to get across to my students is that photography (and all art) is part of a larger conversation carried on by all who have practiced this craft in the past, those who are practicing it now, and those who will practice it in the future. I entered the conversation at Duke University in 1966 when I took my first Art History class. I continued the conversation when my wife and I visited nearly every major cathedral and ever major museum in Europe during the early 70s. And I continue that conversation today as I talk to my students and my photojournalist son, Ben Weller, and as I seek out new photographers on the web such as the amazing work of Brazilian economist Sebastiao Salgado.

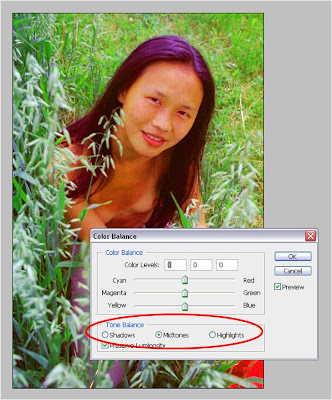

My nude mage is also useful as a classroom demonstration tool because it illustrates an effective use of light (with the only light being the sidelight through the window into an otherwise dark room), the light balance (contrast) is easily manipulated in photoshop. In the image below, I increased both the lightness and the contrast, a net effect which tends to darken the picture but gives the woman greater highlights on her skin while reducing the slight “muddiness” of the original version. What’s neat about having the darkroom set up, is that I can talk about how I could manipulate the picture with polycontrast filters, exposure times and dodging and burning - the students seem fascinated by the darkroom process.

For a PPT version that shows with the click of a mouse the differences between the original version and the Photoshopped version, click here.

And, of course, it doesn’t hurt that we can talk about this picture in terms of the “rule of three” – the image has just three major components: the woman, the window and plant, and the dark interior of the room above and behind her. These three elements are carefully placed and balanced in this picture.