Language Does Not an Argument Make

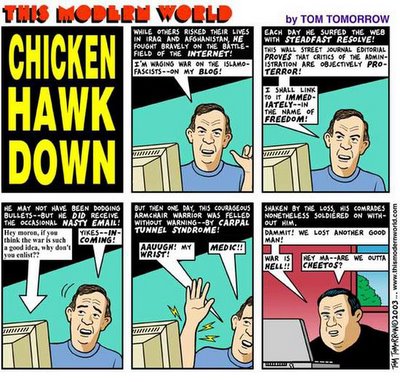

As I alluded to earlier in this blog, language does not an argument make. Take for example the foolish words of the first year Republican Congresswoman from Ohio last week, who impugned the character of decorated Korean and Vietnam war Marine veteran, Rep. John Murtha, because he put aside his hawkish ways and called for a “redeployment” of our troops from Iraq.

Rather than engaging Murtha, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, on the merits of his well-spelled out ideas or on the basis of the actual facts on the ground in Iraq, Rep. Jean Schmidt resorted to the oldest and lowest and most ignorant form of argument, name-calling. Even more craven, she used another traditional and ignoble ploy, the old “straw man” routine, in which the arguer sets someone else up to take the fall if the argument fails.

Standing on the floor of Congress last Friday night, she told her fellow Congressmen and women that she had just gotten a phone call from a “Marine” who wanted her to tell the gathering, in response to Murtha’s unexpected renunciation of the war, that “"cowards cut and run, Marines never do." Following the outcry both on the floor that night and in the press since then, both Schmidt and the so-called Marine have improbably said that’s not what they said (repetition intended), but the implication was clear: Murtha was being labeled in a negative fashion by his opponents, who were unwilling otherwise to engage the strength of his argument.

Now, since this blog is about research and not about politics, lets do a little research. Checking my own favorite blogs first, it didn’t’ take too long to determine that the blogosphere had quickly discovered this so-called Marine was actually a reservist who has never seen combat, and as far as anyone call tell, has never served overseas. It’s not even clear if he has any active duty time; but it is clear that he pulls these kinds of “patriotic” stunts routinely as a low level political operative campaigning with GOP candidates across Ohio. Hardly the qualifications, one might note, to call another Marine a coward. However, this is not my point. My point, also made in an earlier blog, is that in any kind of argument it is necessary to understand the background and the motive of the person at the point of the argument. We can write off Rep. Schmidt as someone whose inexperience caught up with her, but it turns out that this so-called Marine make a career of these kinds of moves.

Moving on, and digging even more deeply into the research, it’s also useful to look at the words used in this argument and to trace their own history and relevance to the argument at hand. With my own recent master’s degree in American Literature, it was easy for me to remember that Ernest Hemingway had a lot to say about this topic. Obsessed himself with a life-long quest in pursuit of “masculinity,” Hemingway nonetheless wrote eloquently and simply (as was proudly his style) about “cowardice” and its inverse, “courage.” A quick google search for “hemingway courage” revealed that the Nobel Prize winning author had this to say about these twin topics: on “cowardice,” he wrote, “Cowardice... is almost always simply a lack of ability to suspend functioning of the imagination.” Note, please, that these words are not just simply eloquent, they also are an argument in themselves.

And here are the breathtaking words Hemingway had to say about courage: “Courage is grace under pressure.” Talking about the power of language, I often tell my composition students that less is more in writing, and Hemingway, for all his faults, is certainly the master of knocking you out with the softest of punches.

So, after this preliminary little bit of research, ask yourself in this case, who had the most grace under pressure, Rep. Jean Schmidt and her so-called Marine friend or Rep John Murtha? As I like to tell my students, the facts will set you free.